You’ve probably seen the headlines, headlines such as: “Churches come tumbling down. . . . Canadian Christendom is destined for history’s sunset.” (Globe and Mail, Christmas 2007)

According to Canadian sociologist Reginald Bibby there is a perception, particularly among academics and the media that religion in Canada is a fossil, a vanishing holdover from an older more superstitious age. Is this so? Has Canada given up on religion, or at least on the Church? That may be the perception, Bibby notes, but the facts say otherwise: “The 2001 census reveals that 84% of Canadians continue to identify with religious groups.” (See The Comeback of Organized Religion in Canada.) What’s more, Bibby’s research suggests that of the remaining 16% who say they have “no religion,” two-thirds will connect with a church when they need religious rituals for children, marriages and death.

And Canadians are still attending church regularly (if somewhat less frequently) at the once-a-month or more level. In fact attendance is on the upswing in the past 5 years—especially among youth!

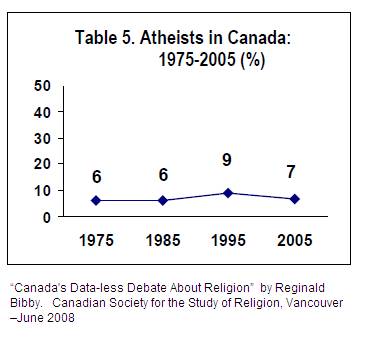

As far as the atheists go, while holding their own, they have about the same grip on Canadian beliefs that they had 30 years ago—very little.

Apparently then Canadians haven’t given up on faith, or even the church. Religion is alive and well in this country. Why is that? What is it that Canadians see in the Church that they aren’t willing to give up—and seem to want more of?

Let me suggest several gifts which the Church has historically offered, and continues to offer, to the building of Canadian society:

Structured support for healthy community values

In one of Project Canada’s studies (see Press Release #10, Oct 8, 2007), researchers compared the attitudes of God-believers to atheists in Canada. They found that on community-building values—such as honesty, kindness, family life, being loved, friendship, courtesy, concern for others, forgiveness, patience and generosity—believers were much more (up to twice as) likely to hold such values as atheists. Bibby suggests that churches provide a place where people can hear the stories, practice the habits, and build the accountable relationships that sustain such values.

Head Space—thinking room that allows for real hope, and the exercise of a rebellious imagination in dealing with community issues

Communities across Canada have been rocked by the recent world-wide economic meltdown. Some fall into a communal depression that sucks away energy for adaptive responses. Churches point them to a God who loves their community and is bigger than the forces assaulting their common life. Christian churches tell the story of a God who saw His Son fall into a nightmare of betrayal, capital charges and death and yet raised that Son to indestructible life. They claim that ancient hates and corrupt states, even the powers of death and hell have no ultimate power over our future because it is held by One who raises the dead. That kind of hope makes it possible to resist destructive trends and try new things, economically, socially, knowing that the effort will not be wasted.

A Talking Place

In the beginning, the “Word” created human community; words continue to build or destroy it. But in a world dominated by great political and economic powers average folks often feel voiceless, helpless to speak words that will make a difference. The church offers a mid-sized space for conversation. It fits between the privacy of family talk and the vast fishbowl of national news media or political debate. It’s a place where people can test out their public “voice” with reasonable risk. And, because Churches tend to draw people together from all walks of life, the conversation is diverse: bartenders and judges, children and engineers, soccer coaches and artists, young and old, rich and poor put in their two cents. Teaching our people how to talk well, providing good processes and healthy structured space for conversation is at the heart of what church and community are about.

Canadian life is a minefield of bureaucratic traps and mazes: income tax, the health care system, banks and finances, the justice system and so on. There are overlapping, intersecting, and often contradictory rules, licenses, fees, punishments and procedures everywhere we turn. Churches have a long history of guiding vulnerable people through those mazes. They help those trapped in the basement of a bureaucracy to get heard at higher levels. They help people sort out complicated applications and legal forms. Church folks sit at hospital bedsides helping people make sense of their journey through illness.

The Rite Stuff

Two recent graduates from our Saskatoon seminaries took adjoining parishes just as two Mounted Police officers were shot and killed in their area. Families and friends of both the victims and accused were members of their churches. These two pastors found themselves thrown into the local and national spotlight. They had to provide a way—a communal liturgy—for people to process the grief and horror of that experience. And so they did. They created opportunities for folks to pray and lament. They modeled ways to be hospitable to media, to care for families. They helped their people channel the powerful but chaotic emotions triggered by the murders into a community-building experience. They mobilized hope and helped the region recover a view of itself as something other than a place that murders its police.

The church was born into drama and liturgy and that is still its central activity. But our rituals are not meant to be private. Public churches take the rite stuff out to their communities. They help celebrate harvests and holidays, lament deaths and disasters. They gather up stories to share at anniversaries and commemorations. They help communities begin things well: through baptisms, weddings, the blessing of new crops, new buildings and, new office-holders. They help end things well: funerals, farewells and closings. And they provide a process for healing and reconciliation from the conflict that a community inevitably suffers.

The church was born into drama and liturgy and that is still its central activity. But our rituals are not meant to be private. Public churches take the rite stuff out to their communities. They help celebrate harvests and holidays, lament deaths and disasters. They gather up stories to share at anniversaries and commemorations. They help communities begin things well: through baptisms, weddings, the blessing of new crops, new buildings and, new office-holders. They help end things well: funerals, farewells and closings. And they provide a process for healing and reconciliation from the conflict that a community inevitably suffers.

A Home Base

The majority of Canadian churches are located in rural and inner city communities that live with constant change and often inferior infrastructure. Rural areas live with boom and bust economies dependent on the vagaries of commodity markets. Inner cities lose their infrastructure to the donut effect, or have it shattered by urban “renewals” which uproot people from their homes and tear long established social webs.

But churches persist. They hang in through the changes brought by weather, markets and government programs. They provide a “home base” for community-building and re-building as they offer: a building; a pastor who knows how to train leaders; a group of volunteers and the know-how to recruit, train and support them; a fund-raising structure and know-how to raise funds; grass-roots memberships that cuts across social lines; a tradition of care for the weakest.

Saving Grace

Gracious churches help their community see that their future is open. It is not simply a reaping of past mistakes or revisiting of past glories. They also help communities value people intrinsically, as God’s creation and not according to their economic production, gender, colour, etc. That grace is essential for the healthy functioning of a community. For example:

The Church has been given some wonderful gifts. They’re meant to be shared. And our country needs them. Let’s take those gifts out where they can do some good!

Cam Harder is Professor of Systematic Theology at Lutheran Theological Seminary, Saskatoon SK. He also directs CiRCLe-M, the Centre for Rural Community Leadership and Ministry at http://www.circle-m.ca/.